Protest encampments have sprung up over the past few weeks on more than 100 college and university campuses across the country, and they have rightly drawn national attention to the pro-Palestinian movement of which they are now an crucial part. A few things seem to be getting lost in the coverage of those encampments, however.

First, while the recent crescendo of activity at colleges and universities has caught the national eye, this movement is not primarily a student or campus-centered movement.

Since October 7, 2023, our project has logged more than 10,000 pro-Palestinian protests nationwide.1 As you can see in the chart below, however, the vast majority of relevant events we’ve recorded over the past seven months—about 7 of every 10—have occurred away from campuses, not on them.

The same is true of arrests made at these events. Of the more than 8,600 arrests we’ve logged at pro-Palestian protests nationally since October 7, about two-thirds of them (5,671 of 8,609) have occurred away from campuses. In other words, far more people have been arrested while participating in this movement away from schools than at them.

One element of the movement driving this pattern is the spread and staying power of routinized actions—demonstrations or vigils that recur monthly, weekly, or even daily. At this point, our project is tracking scores of those nationwide, and they add up to hundreds of events each week. These repetitive actions typically draw little media attention, but they are an important indication of a movement’s salience and staying power. The last time we saw routinized demonstrations emerge and persist at this scale was in 2020, after the murder of George Floyd. These actions typically involve small numbers of people, but, as organizers and participants will tell you, they can have outsized impacts on local and regional politics that persist for years.

Second, this movement has not been violent. That’s true of the broader national wave in general, and of the recent student encampments in particular.

Our project tracks several features of protest events that might be construed as indicators of protester violence, including property damage caused by protesters and injuries to police present at the event. In the more than 10,000 pro-Palestine actions we have recorded since October 7, we have only seen property damage at 128 of them and police injuries at 13. The vast majority of the instances of property damage involved graffiti or similar defacement of property, and virtually all of the police injuries occurred while making arrests. If we look only at actions on school campuses, the incidence of property damage is 30 and police injuries 6, with similar caveats about the what and the how.

Some observers might read the high arrest count as an indicator of violence. In fact, as the chart below shows, the vast majority of arrests have occurred during acts of civil disobedience or direct action that may have disrupted traffic but did not target any people or property for harm. Most of the recent arrests have happened on campuses, but these have generally come in response to concerns about the camp’s purported disruptions to academic life, not any physical injuries they have caused to other people.

In fact, we’ve seen far more violence directed at people protesting for Palestinian liberation or against genocide than we’ve seen from them. The pre-dawn mass assault on the student encampment at UCLA is the most glaring example, but hardly the only one. Just in the past week, we’ve seen people drive cars through crowds of pro-Palestinian or anti-genocide protesters four times, at least one of them causing injury (see here, here, here, and here); a counter-protester wearing brass knuckles push and slap medical students gathering to walk to a rally; a counter-protester brandish a knife at students; a trio of flag-wearing counter-protesters arrive at a encampment before dawn to heckle and verbally threaten students there… The list goes on, and it does not include the scores of uncounted injuries suffered by protesters during police sweeps of campus encampments in places like St. Louis, Los Angeles, and D.C.

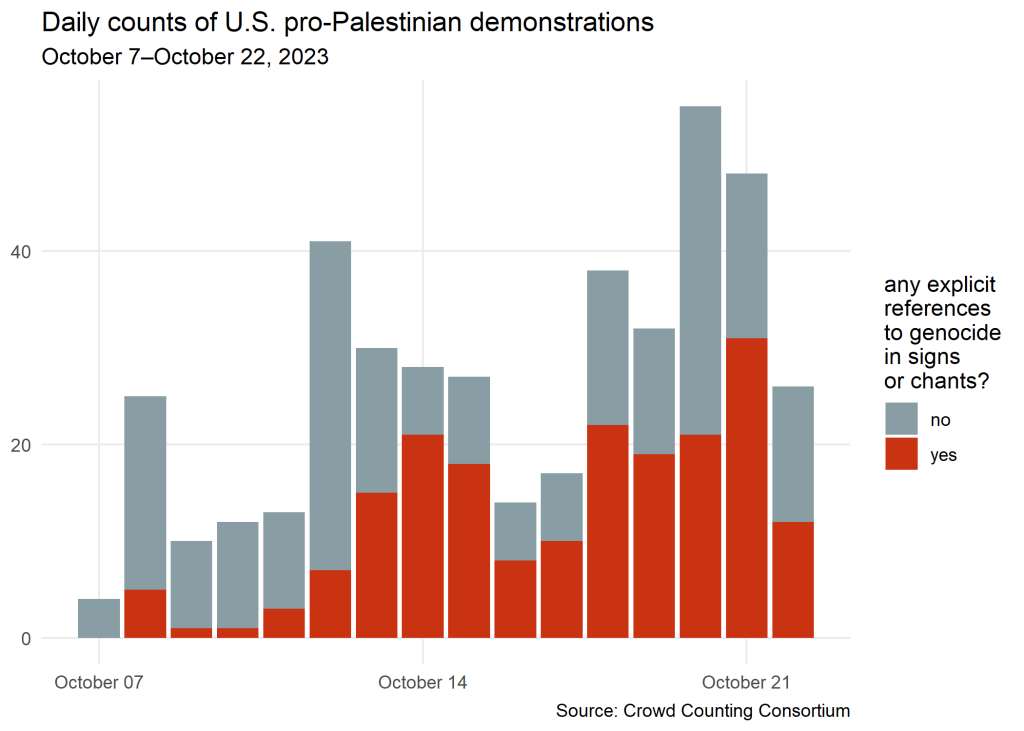

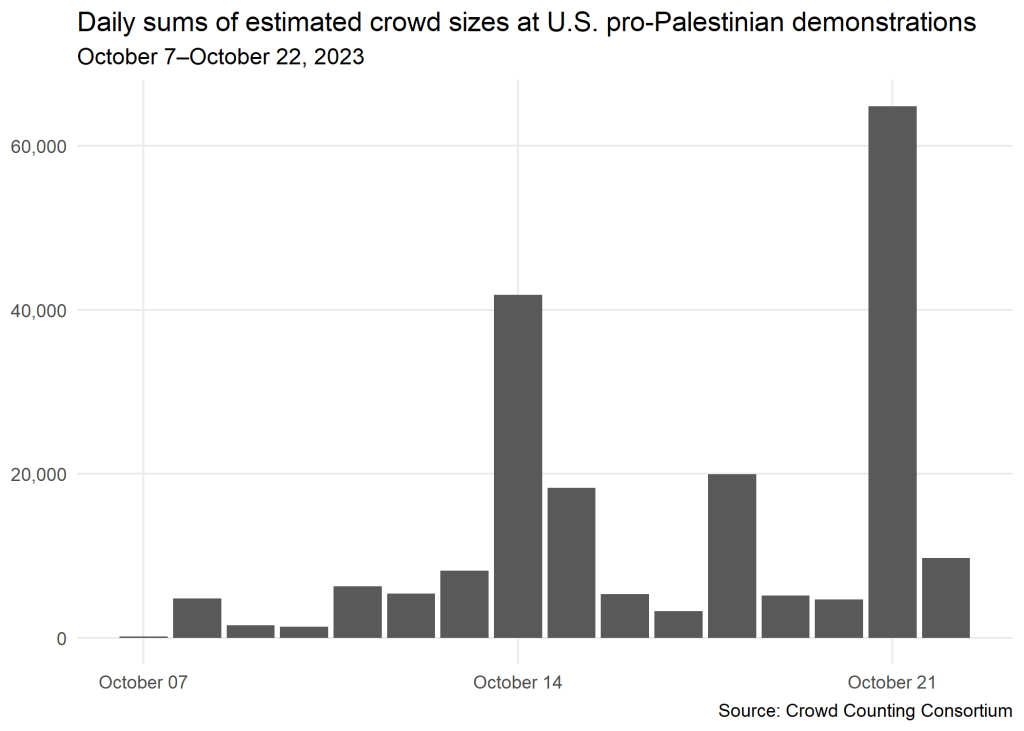

Last but certainly not least, the rhetorical core of this movement has not been a call for violence against Jews, but rather a call for freedom for Palestinians and an end to violence being inflicted upon them.

Take a look at the word cloud below, which shows the relative frequency of the words we’ve seen on banners and signs or heard in chants from these events since October 7.2 The six most common words are Palestine, free, genocide, Gaza, ceasefire, and stop. Based on the thousands of video clips, photos, and dispatches I’ve watched and read from these actions, I would summarize their collective message as “free Palestine,” “stop genocide,” and, more specifically, “stop killing kids,” the latter sometimes with a “…with our taxes/tuition” addendum. When protesters—some of them Jewish, some of them not—have been asked specifically about slogans like “From the river to the sea,” they have almost invariably explained them as positive demands for freedom and human rights and dignity for Palestinians, rather than calls for violence against Israelis or Jews.

There’s much more to say about this movement, of course. In the interest of my time and your attention, however, I’m going to leave it there for now. To stay up to date on what our data show about its persistence and evolution, you can use the interactive maps and dashboards we’ve created to track (crudely speaking) pro-Palestine and pro-Israel protest activity since October 7. And, as always, you can freely download the entirety of our dataset on U.S. protest activity since January 2017, and find more information about what it contains and how we collect it, from our GitHub repository.

-by Jay Ulfelder (May 10, 2024)

FOOTNOTES

- When events span multiple days, as many of the recent student encampments have, we create a separate entry for each day, so we can properly record variation over time in the size and behavior of those actions, and so we properly represent the time and energy associated with them. Technically, then, our overall count is of protest-days rather than separate events, but in the vast majority of cases the two are the same. ↩︎

- Since 2022, our project has been capturing verbatim as many slogans from protesters signs and banners and chants and shouts from protest participants as we can as a way to let protesters describe for themselves what the events in our dataset were about. For any given event, we only record any unique phrase (e.g., “free Palestine”) once, so it’s more of a representative sample of protest claims or ideas than a full capture of protest rhetoric. And, of course, we can’t record chants and phrases we don’t see or hear in the coverage our process tracks. For the word cloud in this post, we only included words that appeared at least 10 times in the nearly 32,000 verbatim claims we have captured from pro-Palestine events since October 2023. ↩︎